Debussy in Jersey by Diane Enget Moore - Page 5

Home Introduction Debussy Biography Jersey 1904 The Blüthner Links

Debussy's "Jersey" Music

We know from research into Debussy’s writing that he did not actually write L’isle joyeuse here in Jersey, he had started work on this piece quite some time before the trip, but he certainly worked on parts of it and revised the title, hence the spelling L’isle instead of L’île, underlining the British influence during this escapade in Jersey. The revisions he made to this piece whilst on the island suggest an added joie de vivre.

Originally, and this is of interest, Debussy intended to compose a trilogy, which would comprise of Masques, L’isle joyeuse and a third piece, probably D’un Cahier d’esquisses, all grouped under the title Suite Bergamasque. In the end, as we know, Suite Bergamasque which came out in 1905, did not include these three pieces, but others, all inspired by Verlaine’s poetry, amongst which was the revised Clair de Lune of 1890, perhaps Debussy’s most popularised piano piece. Clair de Lune is Verlaine’s homage to the early 18th Century painter Watteau:

Votre ame est un

paysage choisi

Que vont charmant masques et bergamasques

Jouant du luth et dansant et quasi

Tristes sous leurs déguisements fantasques.

Your

soul is a favoured landscape

For maskers and bergamaskers enticingly to roam

Dancing and playing the lute,

Almost sad beneath their fanciful disguises.

Debussy, who like Verlaine was a great admirer of Antoine Watteau (1684-1721), found inspiration through his art. One element which constantly appears in Watteau’s paintings is the image of the Commedia dell’arte, masks and bergamasks (a bergamsk being a 16th century dance). We have the juxtaposition of comedy and disguise, comedy and pathos, masks which hide true feelings, and these can either be joyous or sad.

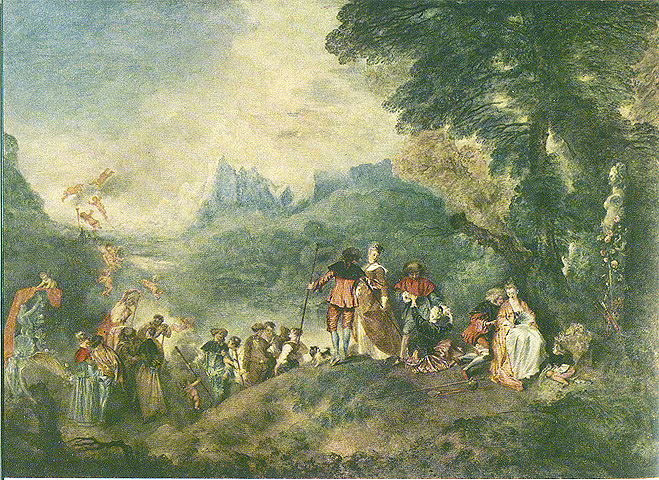

What we do know is that both L’isle joyeuse and Masques, the two works Debussy revised and worked on whilst in Jersey, were both inspired by Watteau’s paintings. L’embarquement pour Cythère as far as L’isle joyeuse is concerned, and Le Mezzetin regarding Masques.

Watteau,

L'embarquement pour Cythère,

©

Musée du Louvre

Let’s have a brief look at L’isle joyeuse and the painting which inspired it. As we know from Debussy’s letter to his editor, he had just completed Fetes Galantes II. The words feste galante are in fact ones which were closely linked with Watteau’s painting L’embarquement pour Cythère when Watteau offered his painting to the Academie Royale. Painted in 1717, Antoine Watteau's The Embarkation for Cythera is long been regarded as one of the masterpieces of eighteenth century French painting. What has often divided art historians, however, is how to interpret the work, especially as Watteau painted a second, more elaborate version, one or two years after the first. At various times the painting has been seen as a symbol of modern disillusionment, a "symphony of nostalgia" with Watteau's message being that in this transitory realm of earthly existence love is ephemeral, fated to pass like life itself. It has also been seen as depicting impossible dreams, the revenge of madness on reason and of freedom on moral rules. Michael Levy has argued that the pilgrims are not in fact embarking for Cythera, the mythical birth place of Aphrodite /Venus, but are preparing to leave it. There certainly does seem to be a basic narrative inconsistency in the work and, as Donald Posner suggests, it is perhaps better not see it as a story or a logical allegorical construction, but instead as a vision of the power of amorous instincts and an intoxicating dream of love fulfilled, with Cythera existing in the human art and thus present both beneath the trees and as an ever-present distant goal.

The mood of Debussy’s music suggests an enchanted landscape, both real and imaginary. As Paul Roberts said, “the real landscape was the island of Jersey, to which Debussy escaped for the summer of 1904 with Emma Bardac: a little prosaic perhaps when compared to Cythera, the mythical island of love in Watteau’s painting, but for Debussy and Emma, a joyous island nevertheless.” The fête galante genre is about love and hope, leisure and flirtation, beauty and elegance, in which wild beauty is not ignored but controlled, just as human desires should be. And for those of us familiar with L’isle joyeuse, the words, “air, lightness and grace” are as central to his music as they are to watteau’s painting. Yet at the same time, l’isle joyeuse is one of those pieces that is well associated with the label impressionistic.

Just as with the Fêtes galantes manuscript which Debussy sent his editor from Jersey, Debussy also inscribed certain pages of L'isle joyeuse manuscript with coded and even direct love messages for Emma: “these bars belong to Madame Bardac pp.m. (petite mienne = little darling) who dictated them to me one Tuesday in June 1904”.

If L’isle joyeuse reflects what the title suggests, air lightness and grace, love and hope, then the other piece Debussy worked on in considerable detail and actually completed whilst in Jersey, can be looked upon as its enigmatic opposite. In fact, as the French pianist Marguerite Long, who at the time of the first world war, had piano lessons with Debussy, wrote of Masques in these terms:

“I hear Masques – a tragedy for piano one might call it – as a sort of transparency of Debussy’s character… He was torn with poignant feelings which he preferred to mask with irony. The title Masques represents an ambiguity which the composer protested with all his might: “It is not the Italian comedy, it is the tragic expression of existence””

The tragic expression of existence? Jersey, summer 1904?

Although L’isle joyeuse might be the island of his own personal idyll, Masques represents the reality that cannot be escaped, the underlying trauma that Debussy knew he had created. The letters to Lilly sent both just before and just after his trip to Jersey, the former not suggesting any break, the latter formally making the break. In many ways, when sitting at the Grand Hotel and completing Masques, he was aware of this dark ambiguity, a premonition of future events almost looming within the music. Let us look at this painting by Watteau, Le Mezzetin. When listening to Masques, let us look at the picture and imagine the situation. The pathetic guitar player, faintly absurd in his commedia costume, yet we are left in no doubt that the hopelessness of his love, symbolised by the cold stone statue facing away from him, has the intense pain of the loss of life itself.

(Watteau, Le Mezzetin, © The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

One interesting thing is that these two pieces, one which was completed in Jersey and sent to Durand from the island, the other submitted for publication after he returned to France from Jersey, were published separately. By then, Debussy had abandoned the idea of publishing them together. The Catalan pianist Ricardo Viñes who performed both pieces at the premiere in February 1905 actually said they both reminded him in some ways of Turner’s paintings. And Debussy replied that indeed he had been fascinated by Turner at the time and is understood to have spent some time studying Turner's paintings on his first visit to London in 1902.

La Mer was composed between 1903 and 1905, and as we know, part of it was written here in Jersey. As we gathered from his letter to Durand, the sea in Jersey was giving him inspiration: “The sea has behaved beautifully towards me and shown me all her guises”… Many critics oversee the role Jersey played in this composition of this orchestral piece, and often it is the visit to Eastbourne which is named when referring to La Mer. (In fact, Debussy also worked on this piece in Dinard). The music of La Mer may conjure up many of the sensations associated with the sea: the titles of the three "symphonic sketches" - "From dawn to midday on the sea", "Play of the waves", "Dialogue of the wind and the sea" - show how explicit the inspiration was. The original inspiration, we learn, came from Debussy’s lifelong passion for all things Japanese (of course “le japonisme” was very much in vogue at the time, and Debussy had a large personal collection of Japanese ornaments and artefacts in his house). And we are to understand that it was this image by the Japanese artist Hokusai, entitled the The Great Wave Off Kanagawa , which gave Debussy the initial burst of inspiration.

(Hokusai, The Great Wave Off Kanagawa, Hakone Museum, Japan.)

Often referred to as Impressionistic, La Mer is a subtle evocation of the sea. Beyond that it also can be interpreted as a profound psychological apprehension of one of the most potent images known to humankind; as with l’isle joyeuse, La Mer is a water piece, and the symbolic connection between water and sexuality is one which cannot be overlooked. When writing La Mer in 1904, Debussy was going through an acute emotional crisis, when concluding La Mer a year later he was deeply attached to Emma Bardac, she was pregnant with his child, the erotic mood having evolved during the course of twelve months. The sea, both in art and in psychology, is associated with the female. If we look at mythology, Venus the Roman goddesss of love, was born from a seashell off the island of Cythera (again an evocation of Cythera as seen in the famous Watteau painting!) One of Debussy’s eminent biographers, Marcel Dietschy, has even suggested that La Mer expresses the composer’s premonition of the personal events to come, that when he started it in 1903 the music expressed a yearning for a love he did not have, and as the composition developed, so did his private life.

Suggested Reading: Paul Roberts, "Images, The Piano Music of Claude Debussy", Amadeus Press, 1996.